Acrolophus is a common genus of moths found throughout most of the United States, with the highest diversity in the East and the Southwest. There are several undescribed species, and identification in the West is challenging due to the lack of available references. However, most of the eastern species are named, and identification from photos is usually possible for intact specimens. This guide is meant to allow for identification of Acrolophus east of the Great Plains. Numerous additional species occur from central Texas west through California which are not included here.

I’ve divided the 16 eastern species into groups:

-Group A: large species (forewing length >1 cm) with small palps pointing directly upward in both sexes (1 species: arcanella)

-Group B: large-to-medium-sized species (forewing length ~1 cm or >1 cm) with palps facing forward to form a snout in females and appearing “combed over” the back of the thorax in males (7 species: popeanella, propinqua, plumifrontella, mortipennella, walsinghami, texanella, and mora)

-Group C: small species (forewing length <1 cm) with palps facing forward to form a snout in females and appearing “combed over” the back of the thorax in males (1 species: simulatus)

Group D: small species (forewing length <1 cm) with small palps (7 species: panamae, heppneri, spilotus, forbesi, piger, cressoni, and mycetophagus)

These are NOT “species groups” in the taxonomic sense, just groups that I’ve placed them into for ease of identification.

Group A:

Arcanella: the only species with FW length >1 cm, a robust thorax, and directly upward-pointing palps that flies in the summer. Some A. mora may have palps that appear upward-pointing in some photos, but A. mora is easy to identify from its flight season (September-October vs May-August for arcanella). These images show the robust thorax (much thicker than the head) and distinctive palps well:

Note that from Texas westward, several other species fit this description as well, such as minor, arizonellus, and davisellus.

Group B:

Mora: Most easily recognized by its late flight season (September-October), long after other Acrolophus in its range have peaked. It is mostly a Northeastern/Appalachian species, flying along with other late-season specialties like Papaipema and Metaxaglaea.Palps are shorter than others in this group, the female’s sometimes not even visible in photos. Warm brown overall with obscure yellow-brown patches along the inner margin.

Walsinghami: The smallest in this group, and the most range-restricted. This is the most abundant Acrolophus by a long way in Penninsular Florida, especially in urban and suburban habitats, but it does not occur over the rest of the East. It typically has a “W-mark” on the forewings and a white discal dot, as seen nicely here:

However, the coloration is extremely variable, with the pattern sometimes being all or partly obscured:

In general though, if you’ve found an Acrolophus at a building light in Penninsular Florida, it’s probably this one.

Mortipennella: Common in the Midwest and Southeast, but rare to absent in the Northeast. Males have exceptionally long palps and a very “dainty” thorax (barely thicker than the head), which means the palps appear to be held well above the thorax, not right up against them:

Females have a distinctive “triangular” look from the side, due to the thin thorax, thin head, and tapering palps:

The female’s palps are shorter than those of plumifrontella, but longer than those of any other females in this group.

Plumifrontella: In fresh condition, the pinkish coloration makes this species unmistakable:

Females are further distinguished by their exceptionally long palps:

Which can unfortunately become damaged or broken off, making the ID tougher:

Texanella: Like mortipennella, mostly a species of the Midwest and Southeast, rare to absent in the Northeast. Structurally, palps are similar to walsinghami, popeanella, and propinqua, but the wing pattern when fresh is usually distinctive: a “stripe” runs from the middle of the costa diagonally to the anal angle in both females (left) and males (right):

The wings are darker distal this stripe. The wing itself is actually creased along this stripe as well, so even in worn or poorly marked individuals, the “stripe” can be seen in the form of a wing crease, like in these:

Melanic individuals, like the right one shown above, often have a few white scales along the crease. White scaling occurs on several other Acrolophus when fresh as well.

Popeanella: A pretty variable species, easily recognized in its yellow-striped form:

That becomes a bit less distinctive in forms where the stripe is darkened:

And sometimes loses the yellow altogether, but the placement of the rest of the patches on the wings remains the same:

In these plain forms, this species can sometimes be very difficult to distinguish from dark specimens of propinqua.

Propinqua: Most common in the Southeast, this is the toughest of this group to identify, as individuals tend to have variable indistinct patches on the wings that approach poorly marked specimens of texanella and popeanella. Here are the “standard” female and male patterns, brown, splotchy, a bit smaller than popeanella, similar to popeanella and texanella in palp structure:

But melanic forms of propinqua are common, especially in coastal habitats. They are usually black with varying amounts of gray, like these:

And sometimes they are completely black with white overscaling, like these:

Group C:

Simulatus: This species is very distinctive, has very long palps in both sexes, and appears to be widespread in the Southeast, with iNat records including most states from NJ south to FL west to TX:

Males:

Females:

Group D:

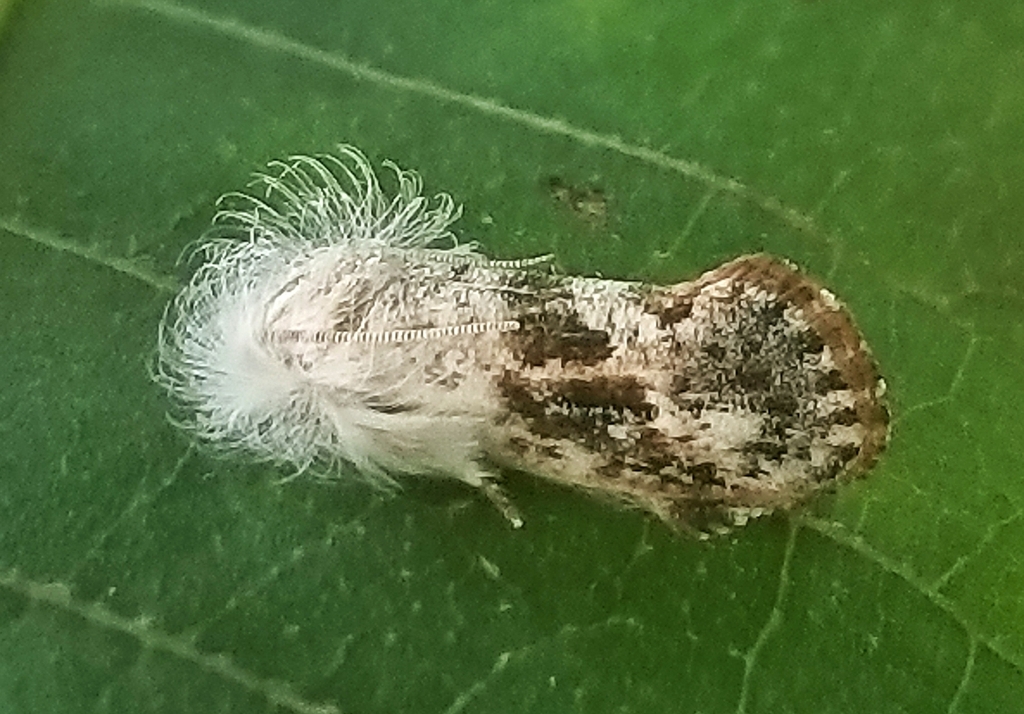

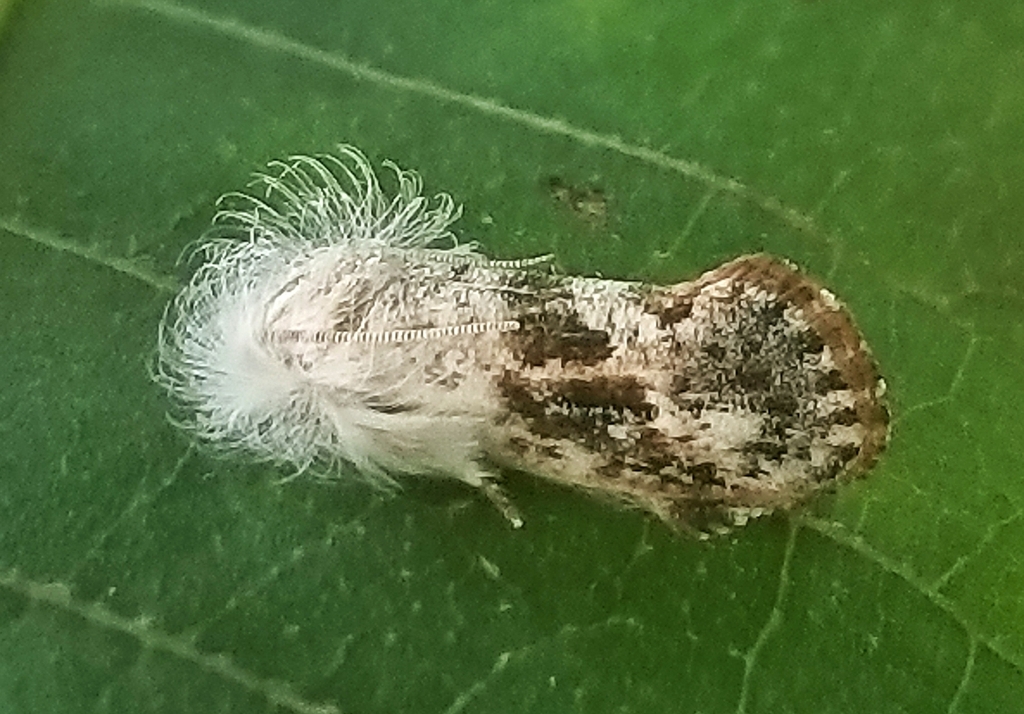

Mycetophagus: Southeastern species, completely unmistakable with huge frills coming off of the forelegs:

Panamae and heppneri also have these frills, but they’re much smaller in those species.

Cressoni: Most abundant in Texas, Oklahoma, and surrounding areas, but also occurs in the Southeast and Arizona. The only small Acrolophus with small palps and raised scales all over the forewings, giving the moth a bumpy appearance:

The only Acrolophus this could be mistaken for in the East is simulatus, but that species has long palps. However, the genus Amydria appears to be frequently confused with A. cressoni on iNaturalist. Amydria has no raised scales on the forewings, which allows it to be separated from cressoni with relative ease:

Panamae: Mostly Southeastern, but occurring as far north as coastal New York State. Small, mostly brown, with some silvery and orange scales (more of the orange becomes visible as the moth fades), with little frills on the legs:

Heppneri: A Gulf Coast species, similar in size to panamae, with the same little frills on the legs, but extremely plainly marked, basically entirely brown except for a dark discal spot:

Spilotus: Apparently a rare species of the Southeast, looks like heppneri but without the foreleg frills and with black speckling overlaying the wings:

Forbesi/piger: Piger is widespread in the Southeast as far west as central Texas, and forbesi is found throughout this same region, but is apparently less common. According to Peter Jump, the species are not separable in photos unless the eyes are seen very close-up- “eyes in A. forbesi are naked or with very short setae and look naked; eyes in A. piger are setose”. So perhaps these shouldn’t be taken to species based on live photos. Here’s what they look like; they’re pretty distinctive among this group:

Males:

Females:

The males have a dark triangle marking on the forewings, and both males and females are more gray than the rest of this group.

And that’s all the Acrolophus one is likely to encounter in eastern North America. Hopefully when a revision comes out, some of the tougher pairs of species will be cleared up a bit.